Loath though I am to admit it, my days in Kyrgyzstan are numbered. I’ve enjoyed nearly every minute of my 10-month stint in Central Asia, and if it weren’t for pragmatic, long-term career-related considerations, I’d extend my stay in a heartbeat. But for now, America beckons. And so, as the sun begins to set on my little adventure in the Switzerland of Central Asia (hah!), I am hustling to check off the remaining items on my Kyrgyzstan bucket list.

Earlier this week, I took advantage of a brief lull in my research to head to Arslanbob, a quaint and sleepy village nestled in the foothills of the Babash-Ata Mountains near the Uzbek border. Arslanbob is known primarily for its walnuts – it’s surrounded by the largest wild walnut forest in the world – but its dramatic setting also draws intrepid adventurers from far and wide. Arslanbob also offers visitors a pleasant taste of Uzbek culture, which dominates the southern half of the country.

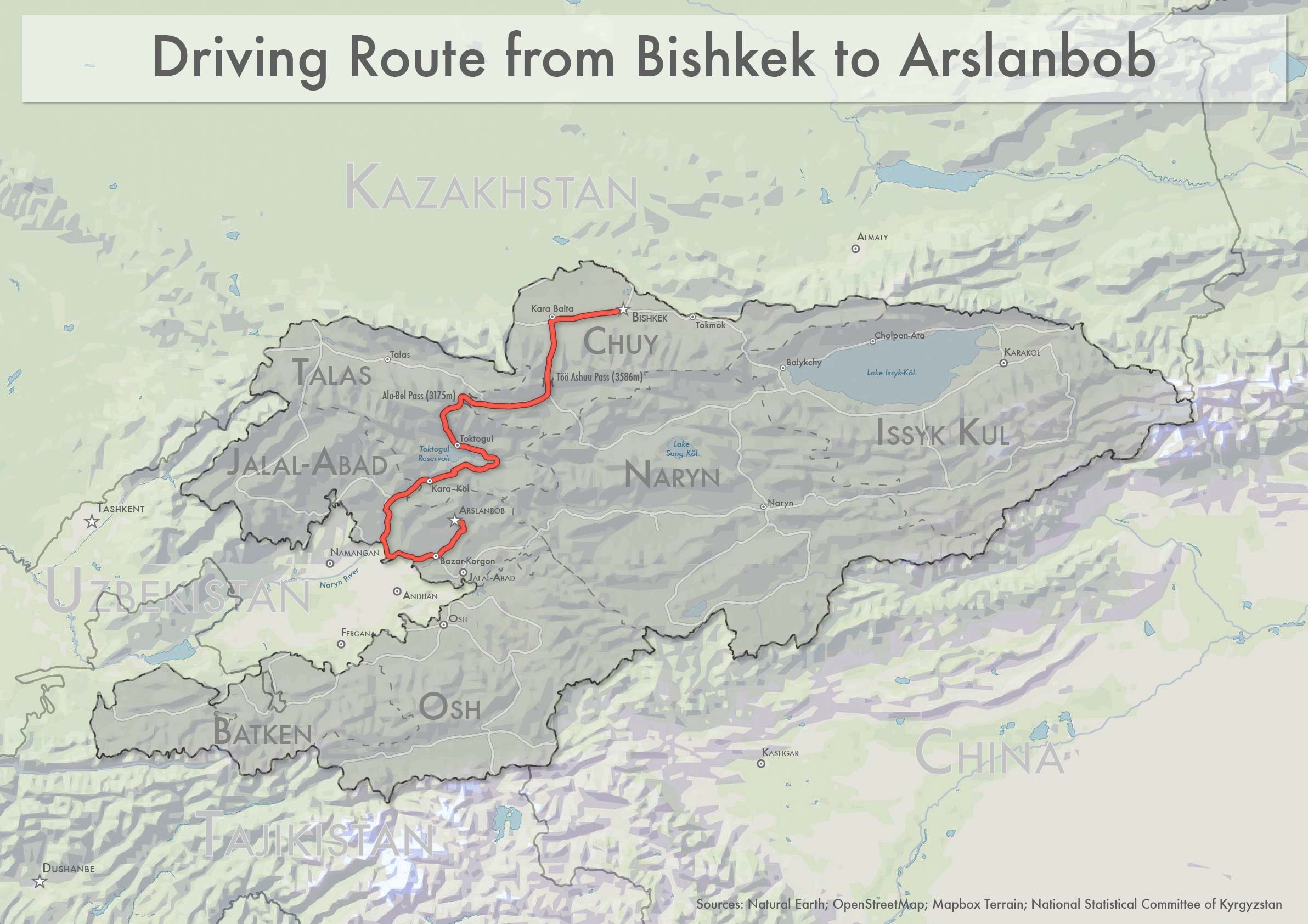

Like most half-decent travelogues, this narrative begins with a description of 10-hour drive from Bishkek to Arslanbob. (In fact, this post only covers the trip to Arslanbob – later this week, I’ll post some thoughts on and photos from my time in the land of walnuts.) The route is, in my opinion, one of the most spectacular one-day drives this planet has to offer. By my reckoning, it’s even better than popular routes such as Austria’s trans-Alpine Pyrhn Autobahn, Russia’s Chuya Highway through the Altai Republic, and even Croatia’s Dalmatian Coast Highway (all of which I had the pleasure of driving last summer). Unlike those roads, this 600-km route passes through several different ecosystems and landscapes, from high alpine pastures to arid red-rock canyons to cotton fields. Like a fine wine tasting, this drive offers travelers a quick sampling of Kyrgyzstan’s spectacular natural scenery, without the commitment and investment of a long-term adventure. It’s not to be missed.

A map of Kyrgyzstan showing the 600-kilometer route from Bishkek to Arslanbob. Click to view a larger version of the map.

The journey began at 9:30am on Tuesday morning when my taxi driver, Furqat, picked me up at my apartment. After collecting our four other passengers – a young Uyghur woman and her infant son, and an elderly Uzbek grandma and her infant granddaughter – we headed west out of Bishkek. I was sitting in the front seat for the drive, and so Furqat and I passed the early hours peppering each other with questions, swapping stories about our homelands, and making fun of each other. It took me a while to understand Furqat’s dialect, as he spoke a curious argot that blended Uzbek, Kyrgyz, Russian, and – when he knew I was listening, at least – American rap lyrics from the mid 2000s. I quickly learned that he, like many residents of southern Kyrgyzstan, spoke Russian worse than I did. Nevertheless, we somehow managed to communicate. Around thirty minutes outside of Bishkek, we stopped at a gas station to top off the tank. As he hopped out of the car, Furqat belted out, “I’ve got 99 problems, and gas is one!” beginning the sentence in English and ending it in his version of Russian. I nearly lost it.

Furqat, my goofy driver to Arslanbob

Some 60 kilometers west of Bishkek, near the town of Kara-Balta (literally, “Black Axe” – badass, right?) lies the northern terminus of the fabled M41 highway. This road is the one of the primary transportation arteries in Central Asia, providing safe passage over the formidable Tien Shan and Pamir mountain ranges. It once formed a critical link on the Silk Road (although it’s unlikely that it was designated Highway M41 at the time) and enabled troop movements during the Great Game. See, not only does this road offer spectacular views, but it’s also steeped in history – it appeals to the bookworms and to the naturalists alike!

From Kara-Balta, we turned onto the M41 and headed due south, toward the perennially snow-covered peaks of the Kyrgyz Ala-Too range. Gradually, we crept higher and higher into the mountains, snaking alongside a turbid brown river, the valley walls slowly closing in on both sides. Suddenly, the canyon opened up onto a sheer mountain face, which we ascended via a series of whiplash-inducing switchbacks. Furqat threw the car into the turns with great gusto, whooping and hollering as we passed slower motorists. I was worried that our top-heavy Honda Stepwgn would tip over, but he managed to keep us upright for the ascent. Eventually, the road leveled out at an altitude of 3,500m. Here, the Töö-Ashuu Pass marked the high altitude point of the trip.

Looking north from the Töö-Ashuu Pass

The pass doesn’t actually surmount the mountains, but rather cuts right through them via a roughly hewn 2.6-kilometer tunnel. Of all the segments of the drive, this one is always the most frightening: the tunnel is so poorly ventilated, and the noxious exhaust fumes so thick, that one can hardly see more than 100 feet ahead. Worse yet, the tunnel is hardly wide enough for two lanes of traffic. In 2001, an accident trapped dozens of cars in the tunnel, and several motorists perished of carbon monoxide poisoning. Cyclists must hitch rides with passing trucks, or risk facing the same fate.

Emerging from the southern end of the tunnel, however, travelers are rewarded with a fantastic view of the Suusamyr Valley extending for miles below. This view is tantalizingly brief, for just as the whole valley comes into view, the road plunges into another rollercoaster of neck-breaking switchbacks, inevitably taken at top speed.

A view of the Suusamyr Valley from the southern (far) end of the Töö-Ashuu tunnel

By this time, Furqat had consumed about four liters of Let’s Go – lemon-flavored sugar-water masquerading as iced tea – and was practically bouncing in his seat. Moreover, he had been furiously chewing nicotine gum since he picked me up. Given the wide availability and popularity of other tobacco products in Central Asia – as well as the astronomical price of nicotine gum – his choice of narcotic struck me as somewhat odd. Assuming the stuff was some bootleg synthetic produced and packaged in a mega-lab in China, I asked where he got it. “Russia, my friend.” Then, taking his hands off the wheel just long enough to throw up some made-up gang signs, Furqat exclaimed, “this is how we do. 50 Cent, you know him?”

The radio wasn’t working, and so we listened to a 10-song collection of Uzbek pop hits. Furqat sang along as best he could – improving ever so slightly with each repetition of the album (10 songs doesn’t get you very far on a 10-hour road trip) – and encouraged me to join in, knowing full well that I didn’t understand the lyrics. Furqat occasionally honked along to the rhythm of the music; in fact, he honked at practically every car and pedestrian we passed – friendly toots, not aggressive ones, always followed up with a grin and a wave.

As we entered the Suusamyr Valley, we passed a hitchhiker heading in the same direction as us. Furqat sped right past him, thought for a second, and then mashed the brakes, bring the van to a standstill. The hitchhiker jogged to catch up, and then breathlessly explained in Russian that he was heading toward Osh, but didn’t have any money. Furqat shook his head, and rolled up the window. As we peeled out, he leaned over toward me, and affecting his best gangster voice, whispered “I’mma tell you like Wu told me, cash rules everything around me” – the hook from a Wyclef Jean song I hadn’t heard since freshman year of high school.

Suusamyr Valley

In the winter, the Suusamyr Valley is practically uninhabitable. In the spring and summer, however, green grass and vegetation carpet the valley floor, and hundreds of semi-nomadic Kyrgyz herders flock (pun intended) to the fertile pastures and deploy their yurts for the season. While the men and boys graze the family flock/herd, old Kyrgyz women peddle gasoline and honey from yurts and trailers along the road.

Locals pose near a Manas Statue, which marks the M41’s junction with the main road to Talas Oblast

Though we had now left the Ala-Too massif behind us, directly ahead, another wall of snowy peaks loomed large. At the southern edge of the Suusamyr Valley, the road again climbed upward toward the Ala-Bel Pass, which sits at an altitude of 3184m. The second pass isn’t quite as dramatic as the first, but it’s still strikingly beautiful. Due to climatic conditions that I won’t attempt to explain (because I don’t understand them), this area is invariably enshrouded in fog and mist, lending it an incomparably eerie vibe. Turbulent streams tumble down the slopes, while flocks of sheep, goats, and cattle lazily munch on the tasty alpine grass.

Yurts dot the mountains near Ala-Bel Pass

Shortly after clearing the Ala-Bel Pass, we stopped for lunch at a roadside chaikhana – coincidentally, the very same one where Benjie, Nick and I ate breakfast a little less than year ago. I enjoyed a piping hot and competitively priced plate of lagman, while Furqat wolfed down two fried trout and a gallon of black tea in as many minutes. (The two female passengers and their kin, who hadn’t yet spoken a word, remained in the car.) Our hunger now fully sated, we returned to the vehicle, and continued our descent toward the Toktogul Basin. The landscape gradually shifted around us, as steep snow-covered slopes and cols gracefully gave way to sparsely vegetated red rock formations.

Once reaching the floor of the Toktogul Basin, we skirted the massive Toktogul Reservoir for a while, its waters dyed a brilliant emerald blue hue by minerals in the surrounding rocks. The reservoir owes its existence to the Toktogul Dam, a massive hydroelectric station (and the biggest power plant in the country) that plugs the Naryn River, a tributary of the Syr Darya. As we sped past the reservoir, I reminisced about swimming in it last summer, eating fresh fish at a waterside chaikhana, and downing shots of peppered vodka with the jovial proprietor.

A stormy sunset over Toktogul Reservoir

All the while, Furqat navigated the road with a deftness and efficiency that inevitably result from extensive experience. He knew exactly where the cops liked to lurk, which dark tunnels concealed potholes, which blind corners were suitable for high-speed passes (read: all of them), which road surfaces were most heavily affected by rainwater, even which kinds of livestock were most skittish. At one point, I jokingly told him that he could probably drive this route blindfolded. Without breaking character, he shut his eyes and carried on driving. I yelped in horror, but he simply took his hands off the wheel, eyes still closed, and commanded, “you drive!” Later, as we approached Arslanbob, he asked if I thought he was a good driver. “Were you scared at all?” I just sort of chuckled.

Driving along the Naryn River

After wrapping around the eastern arm of the reservoir, the M41 broke south, and continued along the sinuous Naryn River, its waters a similar shade of emerald. Gradually, we made our way toward the Ferghana Valley, the lush and tempestuous heart of Kyrgyzstan’s Uzbek-majority south. The rocky outcroppings eventually yielded to fertile fields punctuated by small farming villages with distinctly Soviet names, like Truth (Правда/Pravda), Friendship (Достук/Dostuk), Red October (Кызыл Октябрь/Kyzyl Oktyabr), and First of May (Первое Мая/Pervoye Maya).

Hills and fields at the northern edge of the Ferghana Valley

We turned off the M41 near Bazar-Korgon, and began the final approach toward Arslanbob. This leg led us through lumpy green hills, whose curiously bulbous shapes wouldn’t look entirely out of place in a Dr. Seuss book. Every five or ten miles, we encountered flocks of sheep lazily wandering along the road. At one point, Furqat advised me semi-seriously to open the door and grab a lamb to cook for dinner. I politely declined, not wishing to offend the toothless shepherd guiding his flock from the comfort of a donkey.

Hills and herds near Arslanbob

Finally, the road turned north again, toward the Babash-Ata Mountains, another arm of the Tien Shan. There, nestled in a narrow valley bisected by a tumbling river, sat the sleepy village of Arslanbob. Our progress slowed as we approached the village, for Furqat had to stop and shake hands with various passers-by. At one point, he leaned out of the window and tossed a wad of bills to a middle-aged woman walking by. Ducking back into the car, he explained to me, in his curious broken Russian, that the woman was his sister, and he was giving her her allowance. And then, in one last lewd ode to American rap, he quoted Kanye West: “I ain’t sayin she’s a gold digger, but she ain’t messin with no broke n****s.” I had no response for him – just laughter.

And so, ten hours after setting out from Bishkek, we arrived at our destination. I paid Furqat for the ride, shook his hand goodbye, and set off in search of the CBT office (that’s Community-Based Tourism). However, I didn’t make it more than a couple yards before Furqat hailed me. “Call me if you need a ride back to Bishkek,” he hollered. “Next time, you can drive!” I briefly considered whether I had the mettle to excel as a shared taxi driver in Kyrgyzstan. Shaking my head, I turned to him and responded with a grin, “only if you pay me for the ride!” and then continued on my merry way.

A panoramic view of the Babash-Ata Mountains overlooking Arslanbob

Join me later this week as I recount my adventures in Arslanbob. Featured guests include an old Uzbek man claiming to possess magical powers, a trio of gold-toothed rapscallions, a roofless UAZ jeep, and a Bactrian camel. ‘Til then, folks!

Comments are now closed