Previous entries in my “Buildings That I love” series have focused exclusively on the Kyrgyz capital’s Soviet Modernist structures: those imposing, brutish, austere buildings that evoke strength rather than grace. In this installment, however, I’ll introduce you a slightly older, and immeasurably more glamorous, architectural style: Stalinism. Like Soviet Modernism, Stalinism was not just an aesthetic, but an entire philosophy. Developed in concert with other instruments of the Soviet propaganda apparatus, Stalinism sought to illustrate the Soviet Union’s (re)ascendance to greatness. Whereas Soviet Modernism aimed to emphasize the USSR’s strength and unity, Stalinism cast the USSR as an enlightened, sophisticated sociopolitical body. Stalinist structures were unapologetically grand, ornate, and often built on a scale previously unseen in the USSR.

The finest exemplars of this architectural style are Moscow’s Seven Sisters (in Russian, Сталинские высотки, or “Stalinist Skyscrapers”), a group of high-rises built between 1947 and 1953. (Incidentally, one of the skyscrapers, Moscow State University, is one of my favorite buildings of all time, even though I’ve never seen it in person.) While Stalinist buildings are understandably concentrated in the cultural and political centers of the Former Soviet Union, the architectural style was also exported to the farthest reaches of the Soviet Union. This post explores not one, but three of Bishkek’s finest Stalinist buildings: Bishkek City Hall (formerly the headquarters of the City Executive Committee), the Promstroi Bank (formerly the Ministry of Agriculture), and the International University of Kyrgyzstan (formerly the Kyrgyz Polytechnical University). These three buildings sit astride Chui Avenue, the city’s primary east-west axis, and represent the first planned ensemble of public buildings constructed in Soviet Bishkek (err, Frunze). It’s clear that the buildings were designed in concert, as they display a common visual language.

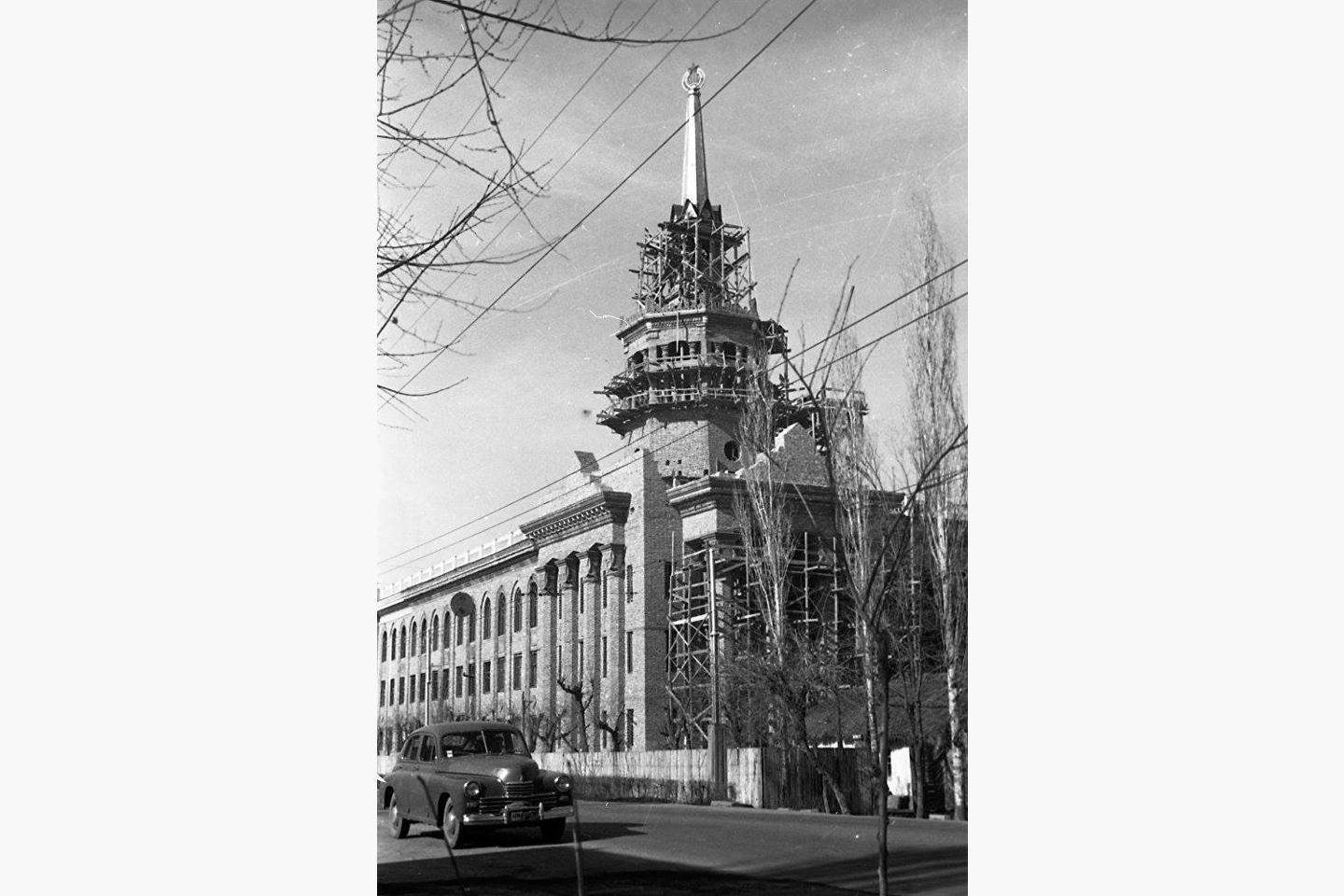

An old postcard of Bishkek featuring the Stalinist Ensemble at Soviet Square. Notice the lack of a spire on the Ministry of Agriculture building.

Unfortunately, I don’t have too much information about these buildings—or original photos, for that matter. What I do know is that all three buildings were constructed between 1951 and 1959, during the twilight years of Stalinism. In 1953, Nikita Khrushchev, Stalin’s successor, publicly decried the “excesses” of the Stalinist style, and threatened to halt the construction of any unnecessarily ornate structures. This decree imperiled Bishkek’s City Hall which, at the time, was roughly halfway complete. Fortunately, the building’s lead architect, an ethnic Russian named Pavel Petrovich Ivanov, had previously served as the first Chief Architect of the Kyrgyz SSR. A man of considerable political clout, Ivanov was well connected with the Soviet Politboro in Moscow. So, he did what any self-respecting communist official would do: he called in some favors, maybe greased some palms, and rescued the City Hall project, to which he’d grown personally attached, from almost certain abandonment. Good work, Pavel.

The building has changed little since its construction, save for a new turquoise paint job (the building was originally white). A wide portico, supported by six elegant Corinthian columns, dominates the front of the building. Adorning the triangular pediment is a large cast of the Kyrgyz national emblem, reminding passersby of the building’s government affiliation. Ornamental cornices, shallow pilasters, and decorative pelmets above the central windows all contribute to the structure’s stately appearance. A slender spire extends from the crown of the building, bearing a simple five-pointed star, a conspicuous reminder of the building’s Soviet origins. On clear days, the blue Tian Shan mountains loom behind the building.

Adjacent to City Hall is the former Ministry of Agriculture, which today contains the Promstroi Bank. Though slightly less ornate than City Hall, the three-story building still stands out against the backdrop of apartment buildings, thanks in part to its pastel pink coloring. The building’s eastern and northern sides—which face City Hall and the University, respectively—contain four-column porticos and thick ornamental cornices. A decorative spire has since been added as well. Incidentally, Stalin was said to have a strong affinity for spires, which partially explains the preponderance of this architectural element on post-war buildings, although the Promstroi Bank’s spire was added after his death.

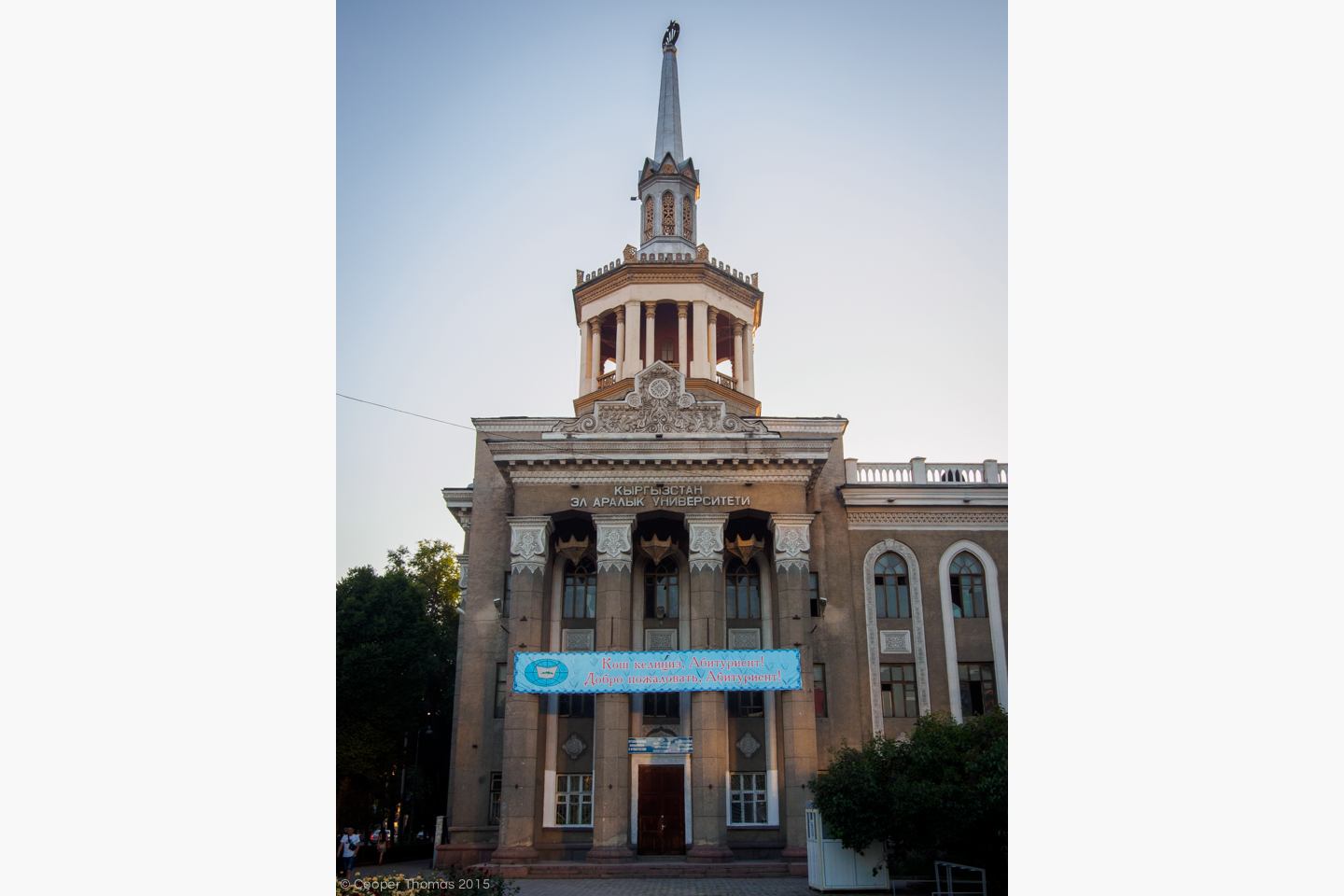

Across the street sits the International University of Kyrgyzstan, originally constructed as the National Polytechnical University. This building, the last of the three to be completed, is also my favorite. It sports an unpainted cement exterior (including its four-column portico), but the most richly embellished pediment and cornices, which feature bas-relief rosettes and geometric swirls. The university’s spire is considerably stouter than that of the Promstroi Bank, and more elaborately embellished, and while I’m not sure if it has any functional purpose (roof lantern, maybe?) it’s surely the most attractive feature of the building.

Much of the building is enshrouded in shrubbery, and I haven’t been inside, so my impressions of the university are based pretty much exclusively on the southeast corner of the structure. Poor reportage on my part, I know. But I just couldn’t resist sharing this gem.

Together, these three buildings once formed the southwest elbow of Soviet Square. Today, the space is dominated by the monolithic National Philharmonic building (added in the early 1980s), while the three Stalinist buildings have relegated to monuments of secondary importance (at least visually). Nevertheless, they still exude a sort of classy, refined vibe that you don’t readily feel in most other parts of the city.

Share Your Thoughts