Dear friends: on Monday, I wrote a detailed report of my visit to Arslanbob, but I somehow managed to delete the whole thing. Maybe I’ll get to recreating it eventually, maybe not, but in the meantime, here’s a considerably shorter and disjointed write-up for your amusement. Plus some pictures.

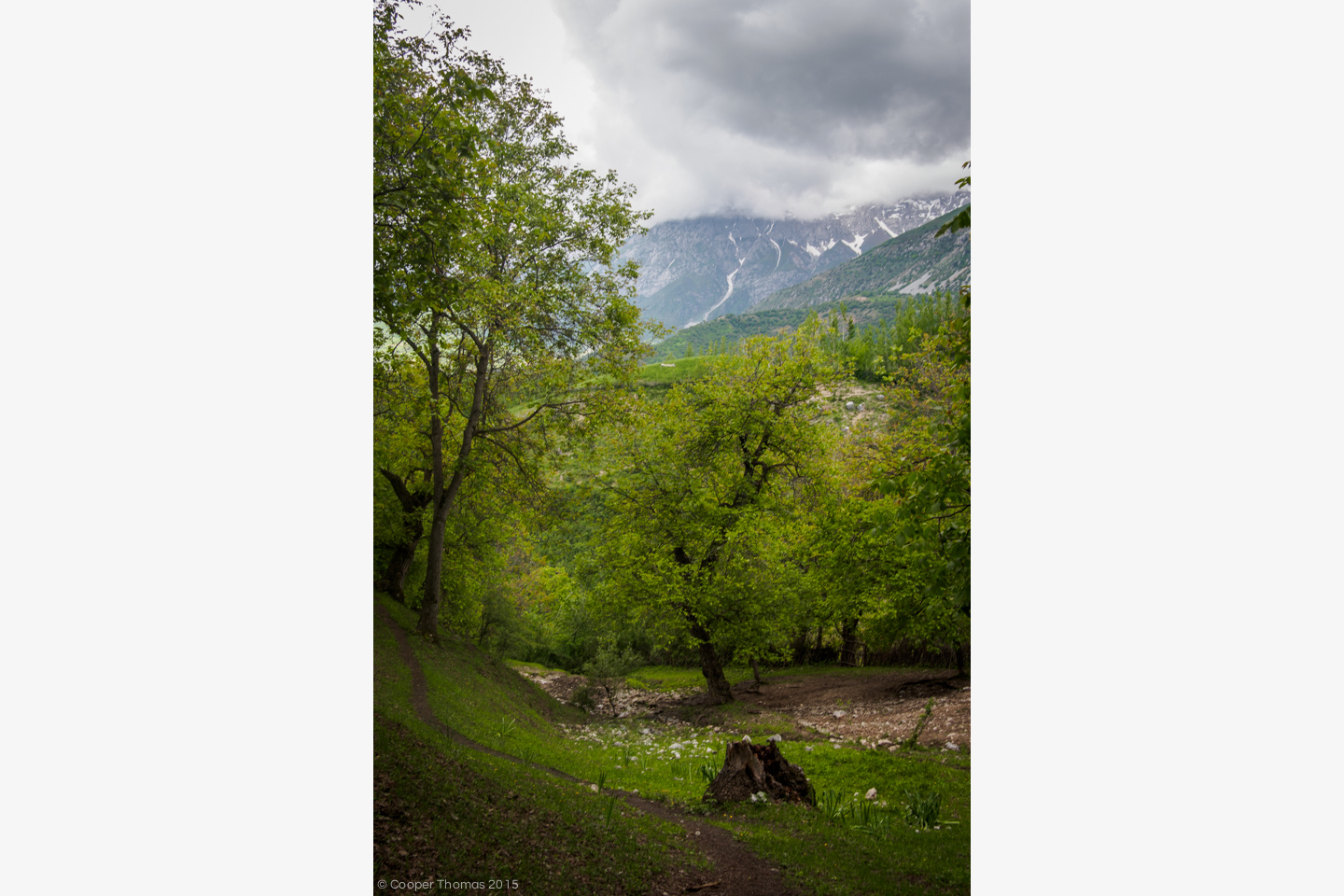

A view of the Arslanbob Valley. This ultra-wide-angle shot exaggerates the distance between the mountains and the village; in reality, they’re much closer.

Arslanbob sits in a narrow valley in the southern foothills of the Babash-Ata Mountains, a stretch of the Ala-Too Range that protrudes like a spine along Kyrgyzstan’s east-west axis. Since Arslanbob is perched on a gentle incline, the mountains are visible from almost every point in the village, casting soft shadows that lazily meander across town as the sun processes through the sky. Most of the residents live in low, wattle-and-daub or mud brick houses, painted cheery colors to camouflage the rustic construction materials. The village spreads out out over a broad area, and small vegetable gardens and fields, demarcated by stone walls and gates, encircle many residences.

The guesthouse where I stayed

Looking north toward the Babash-Ata Mountains from the guesthouse backyard

I love the graphic on this gate – it’s a total knock-off of the 1980 Olympus logo

Arslanbob has an unmistably bucolic vibe. Donkey carts tumble up and down the streets, young girls draw water from wells and streams, and livestock and domesticated critters roam untethered through the village. During my brief visit, I encountered cows, goats, sheep, donkeys, horses, dogs, cats, chickens, and ducks in the street. At one point, an unattended Bactrian camel even wandered past my guesthouse, pausing long enough to munch on some greenery and snort at me indignantly. Many Muslims, including Uzbeks and Kyrgyz, believe that camels are such exceptionally smug animals because they know the hundred different names of Allah, whereas humans only know 99. Oh, to be a camel!

The friendly neighborhood Bactrian

Arslanbob is surrounded by the largest wild walnut forest in the world, and deez nuts the nuts feature prominently in local lore. Legend has it that the Prophet Mohammad sent one of his disciples on a mission to find paradise on earth, and equipped him with a sack of walnuts to fuel him during his journey. (Few people know that Mohammad was an accomplished nutritionist, and was well aware of the walnut’s innumerable health benefits.) Our intrepid protagonist eventually stumbled upon this very valley, but found it utterly devoid of vegetation. Nevertheless convinced that he’d found paradise on earth, he summited Babash-Ata Mountain, and cast a nut in every direction, thus sowing the seeds of the vast walnut forests that cling to the mountainsides today. I think there’s a big-budget action-adventure screenplay in there somewhere.

Today, the walnut is a staple of the local economy, and nearly every family participates in the annual nut harvest. Locals even accept these nuts as hard currency, from time to time. But the town has also developed into a regional hub of small-scale trade, and every Wednesday, vendors from Jalal-Abad, Osh, and even Bishkek descend on Arslanbob to peddle their goods at the weekly bazaar. Overnight, the sleepy village is transformed into a bustling hive of activity, as locals haggle over the consumer goods and foodstuffs not sold in the village’s four general stores. Below are a handful of photos from the bazaar.

On hot days, locals flock to Arslanbob’s twin waterfalls – the aptly named Big Waterfall (Большой Водопад) and Small Waterfall (Маленький Водопад) – to cool of in the misty spray. The waterfalls themselves are unremarkable, but the sites are great for people-watching. The paths leading down to the waterfalls are flanked by small stalls selling snacks and kitschy souvenirs for locals and domestic tourists. Most of the stalls stood vacant during my visit, but apparently, they fill up during the summer months.

The small waterfall, at a distance

Empty stalls near the small waterfall

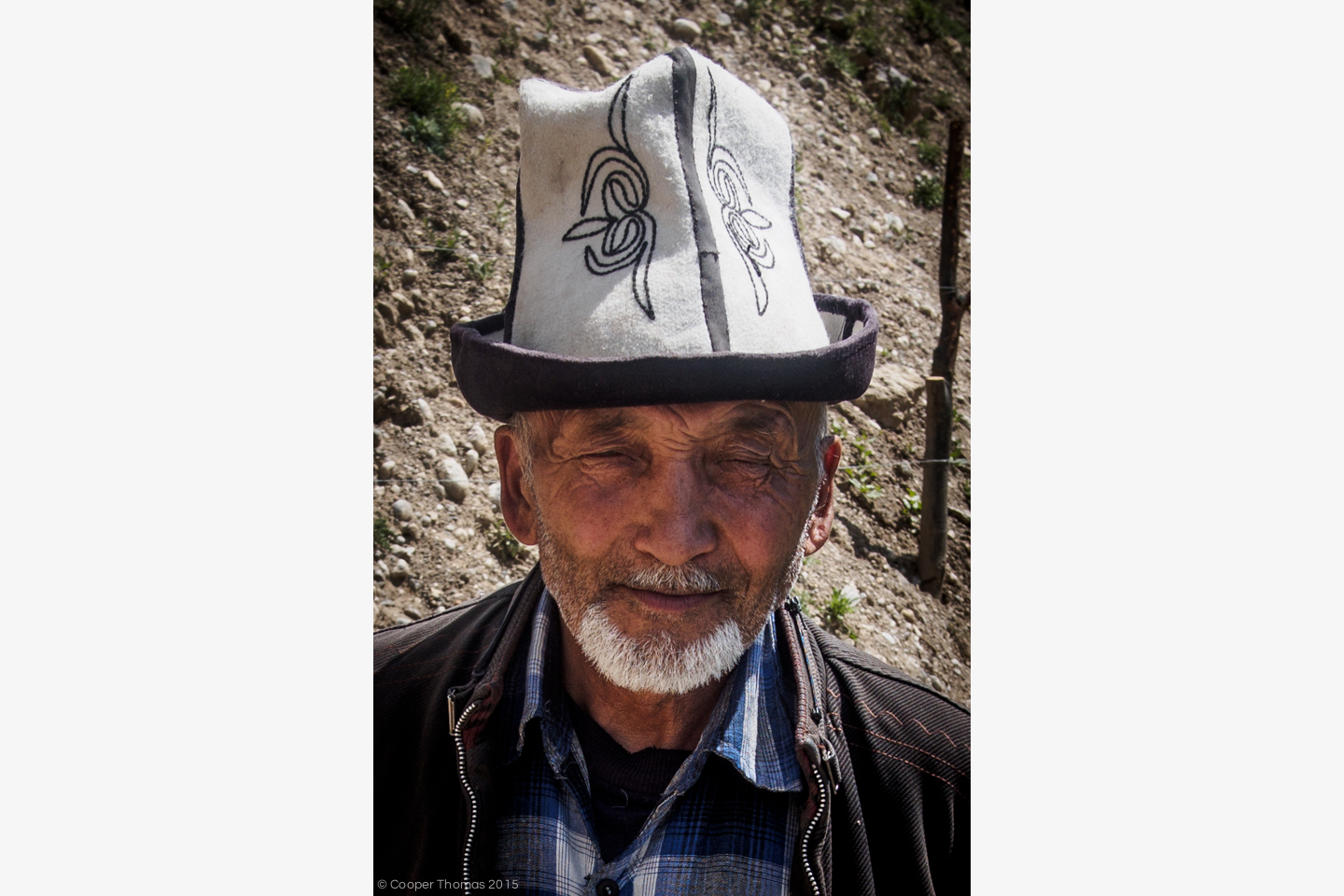

While wandering around the small waterfall, I met the kalpak-sporting chap in the image below. He told me that the waterfall is surrounded by prayer caves that imbue devotees with long life and supernatural powers. He told me that he was 200 years old, and that he’d lost a leg in World War II but re-grew it after visiting the caves. I asked to see his leg, but he told me he couldn’t show it to me because I wasn’t a Muslim. I conceded defeat, snapped a photo upon his request, and continued on my way.

I stayed in a small guesthouse arranged by the local CBT office. My host, Nazigul, was a kind, motherly widow of around 40 years old. Her two youngest sons, Anarbek (3) and Mohammadi (4), were full of energy, tearing around the property on their miniature jeeps from dawn until dusk. Also living in the house were a sullen teenage boy and a quiet teenage girl – both Nazigul’s children, I think (or maybe a young couple?) – two old female aunts, and a wizened grandfather, the de facto paterfamilias. Each morning, as the two of us waited for the women to prepare our breakfasts (as one does in Arslanbob), he regaled me with colorful tales from his time serving in the Red Army in East Germany. I asked to take his photo, but he was concerned that the camera might take his soul. So I pointed it at the youngins instead.

Mohammadi, prince of the guesthouse

Most residents of Arslanbob are ethnically Uzbek, and share more in common with their sedentary neighbors to the west than the semi-nomadic Kyrgyz of the Ala-Too. Few here speak fluent Russian, but despite the language barrier, all the locals I met were exceptionally warm and welcoming. Many asked me about life in America – what most people earn, whether students learn about Uzbek history in school, how much (and whom) one must pay to ensure that one’s visa application is accepted, whether I know so-and-so’s cousin Omurbek who lives in New York City.

Locals enjoy a typical Uzbek lunch of meat, bread, and tea

On my second evening in Arslanbob, as I was casually strolling around the village, I came across a trio of young Uzbek guys sitting on small cushions in an open field, nursing a plastic 2-liter of cheap beer and nibbling fresh kurut. The they introduced themselves as Hassan, Adyl, and Kamal, and explained to me that they were celebrating Hassan’s 30th birthday. They invited me to join them, and I happily obliged. These guys hardly spoke Russian, and so Adyl, the most competent of the three, proudly assumed the role of interpreter. Whenever we encountered a linguistic impasse, he’d simply point at Hassan, repeat a single sentence – “сегодня, его день рождения!” (“today’s his birthday!”), pronouncing the words exactly as they are written, to my initial confusion – flash his gold teeth and howl in laughter.

Hassan sits behind the wheel of his trusty UAZ-469

It soon began to rain, and so we piled into Hassan’s rusty UAZ 4×4, a mechanical relic of the Warsaw Pact days of yore. The SUV didn’t actually have a roof, and so Hassan hastily pulled a piece of clear plastic over the roll bars, untied his sneakers, and used the shoelaces to lash the tarp down. These cheap Soviet machines are quite poorly constructed, and Kamal had to use a mechanical crank to turn the engine over. We rumbled down the hill to the central square, where I purchased two more bottles of beer as a gift for Hassan. We then proceeded to a quiet street to drink our beers in peace. They warned me not to speak too loudly, in case the cops heard us. Hassan didn’t imbibe, since he was driving. As Adyl explained to me, “we drink for him on his birthday!” I told him that this seemed like an unfair agreement, to which he responded, as if on cue, “today’s his birthday!”

Eventually, they asked me where I was staying. When I uttered the name of my host, all three sat bolt upright in their seats. “She’s my neighbor,” exclaimed Adyl, fidgeting nervously. “If she asks, you had no problems with us tonight, okay?” I assured them that I wouldn’t rat them out, and they relaxed. The whole thing reminded me a bit of my own high school hijinks, only these guys were 30! Shortly before dark, they returned me to my guesthouse – parking a hundred feet away from the gate, so that Nazigul wouldn’t hear the car – and wished me luck. I returned the gesture, and told them to come find me if they were ever in the United States. They nodded vigorously and sped off.

Two days later, back in Bishkek, I received a Facebook friend request from Hassan, along with a message in crude Russian. “Don’t forget us,” the first line read. “And if you find a spare UAZ roof in Bishkek, could you send it to this address?”

Share Your Thoughts